Korean identity: a story of genetic continuity 1,400 years in the making | Razib Khan

Korean is a language isolate:

body

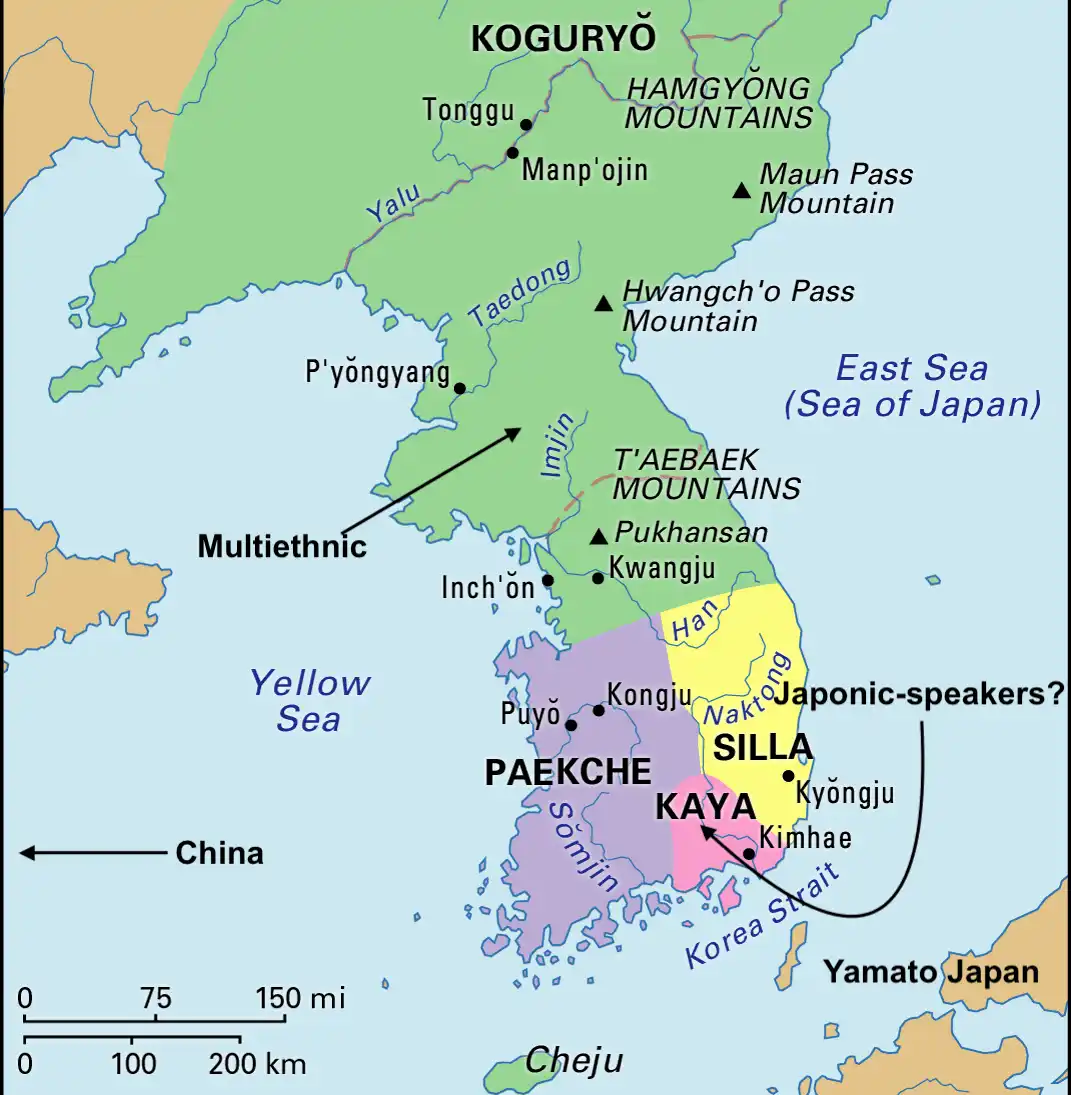

Korea 500 AD

The Korean Peninsula is a geographic nexus point. At its narrowest, the peninsula is just 144 miles across. Surrounded by the Yellow and East Seas on three sides, it descends delicately in organic irregularity from the Asian mainland’s easternmost reaches like a healthy lobe of ginger. To its west, across the Yellow Sea, begins the vast landmass of China's core provinces and to its east are the many islands of Japan. But just as importantly, to the north is Korea’s sole land connection with the rest of Asia, the vast mixed territory of forests, lakes and grasslands that is Manchuria. Following the Manchu conquests of China in the 17th century, the tables turned and successive waves of Han Chinese settlers transformed Manchuria into a northeastern appendage of China. The fallen Chinese, a subject race, conquered their Manchu overlords and the Manchu homeland through sheer force of numbers; ancient Manchuria faded into the annals of history in the era when the American republic was just emerging, going from a land of a hundred tribes to just another Chinese province.

But Manchuria’s unrecorded history holds many of the keys to Korea’s past. Today, the Yalu river sharply delimits the boundary between the communist People's Republic of China and the communist Democratic Republic of Korea. However, where Korea began and Manchuria ended has traditionally been more vague; Koreans and Manchurians have mixed and migrated across each other's lands since before the end of the last Ice Age. The makeup of Koreans, both today and historically, according to ancient DNA, suggest these interactions were a dynamic two-way engagement. Korea’s occupation of a unique central geographic position in Northeast Asia, and the nation’s track record of existential battles for supremacy and survival made the peninsula a merciless, competitive arena. Over the last few millennia, Korea has proven a demographic cul-de-sac where the winner takes all and it’s either up or out, but with “out” generally having all the finality of a Roman gladiator’s first loss, a culling field from the Yalu in the north to Straits of Tsushima in the south. Many people entered, but only Koreans were left standing in the end.

The outcome of this roiling history is a Korean identity and underlying genetics that exhibit a stability and continuity rarely seen elsewhere on the planet. But only by examining the macro-regional history that extends far beyond Korea can we reconstruct the peninsula's past. We must look north to Manchuria, a land until recently of illiterate tribes. And west to ancient China, with its vaunted history going back over three millennia. And finally, we must look east to Japan, a nation with an inextricable connection to Korea, but which pointedly insists upon its separate uniqueness. Two hundred miles east across the Korea strait, Japan appears to be the repeat forward destination for the genetic imprint of prehistoric Korean migrants. This reality is the outcome of the Korean peninsula’s role as both a sieve and a demographic escape valve for the Japanese archipelago. Korea, then, is perhaps an extreme case of geography guiding and straitjacketing history in a nation-state I have yet examined here[1].

But this non-negotiable geography interacts with the fluid contingency of history. In 668 AD Silla, a domain coterminous with modern South Korea, led by its king Munmu, defeated a centuries-long rival, the Koguryo kingdom of the north. This momentously unified most of the Korean peninsula into a single state, an event which ushered in the Korean nation we still know today. Consider that by comparison, in that year Britain was divided between seven Anglo-Saxon kingdoms fringed by half a dozen Celtic principalities. In continental Europe, what would become France was split into numerous duchies, as powerful local potentates relegated the seventh-century kings to ceremonial figurehead status. But except for one brief interlude of fragmentation between 892 and 936 AD in the wake of Silla’s dissolution, the Korean peninsula was destined to remain a unified state from that moment forward, not to be sundered again until 1953. The Koryo dynasty, from which the name Korea derives, reunified the peninsula in 936 once and for all, handing power in 1392 to the +Choson dynasty. They ruled all the way until 1910, when the Japanese integrated Korea into the Japanese Empire, temporarily dissolving the nation-state.

The totality of Silla’s conquest fatefully closed the door on any future possibility of a peninsula with a multiplicity of ethnicities; the Korean peninsula, which in the depths of the Ice Age and down to the centuries after the birth of Christ, had been a byway of peoples from Manchuria to Japan, was instead destined to become one of the most homogeneous nations in the world.

The diverse cultural and genetic foundations of Korea predate 668 AD. But the 1,400 year continuity of a national identity across Silla, Koryo and Choson permanently interwove those threads, and goes a long way towards explaining contemporary Koreans’ shared sense of belonging, and that they are one people and one race. Most post-colonial states that arose out of the detritus of fallen modern empires are but decades old, while Korea is long past its first millennium of existence. There are, of course, other models of national identity and self-conception than Korea’s. In Germany, the preexistent nation called the state into being. In the Indian case, the administrative state created the national political identity in the 20th century. For Koreans, like their Japanese neighbors, the ethnic nation and the administrative state are inseparable, co-evolving together. To be Korean is not simply a legal writ or geographical coincidence (though both have their roles). It entails Korean ancestry and culture. Neither is Korea a legal mandate, summoned into being by will and colonial caprice (like Taiwan or many African nations).

Korea’s geographic outlines go back to the dawn of written history in northeast Asia 2,000 years ago, when Imperial Chinese chroniclers of the Han Dynasty recorded the proto-Korean tribes, the Buyeo (in central Manchuria) and Yemaek (in southern Manchuria and northern Korea), among the various barbarians brought into the fold of the Middle Kingdom. For centuries, Imperial texts referred to Manchuria and the lands that are today North Korea as the barbarian commanderies of the northeast. Silla’s political unification would smooth out the peninsula’s ethnic landscape, but the earlier diversity of peoples, some related to the modern Japanese and the Ainu of Hokkaido, others to Manchurian foragers, farmers and herd[er]s, can still be discerned in the Chinese texts, archaeological evidence and genetic record. Korean history is partly a story of those early inhabitants’ assimilation into the genetic patrimony of modern Koreans and integration into Korea’s culture and ruling class. Today Koreans share a land border with Manchuria, which until recently was ethnically very diverse, but deep in their shared past, Korea also contained multitudes, both streaming in from the great north, and moving onward to the islands of the east.

Asian Genetics

A Northeast Asian map of Korean genealogy

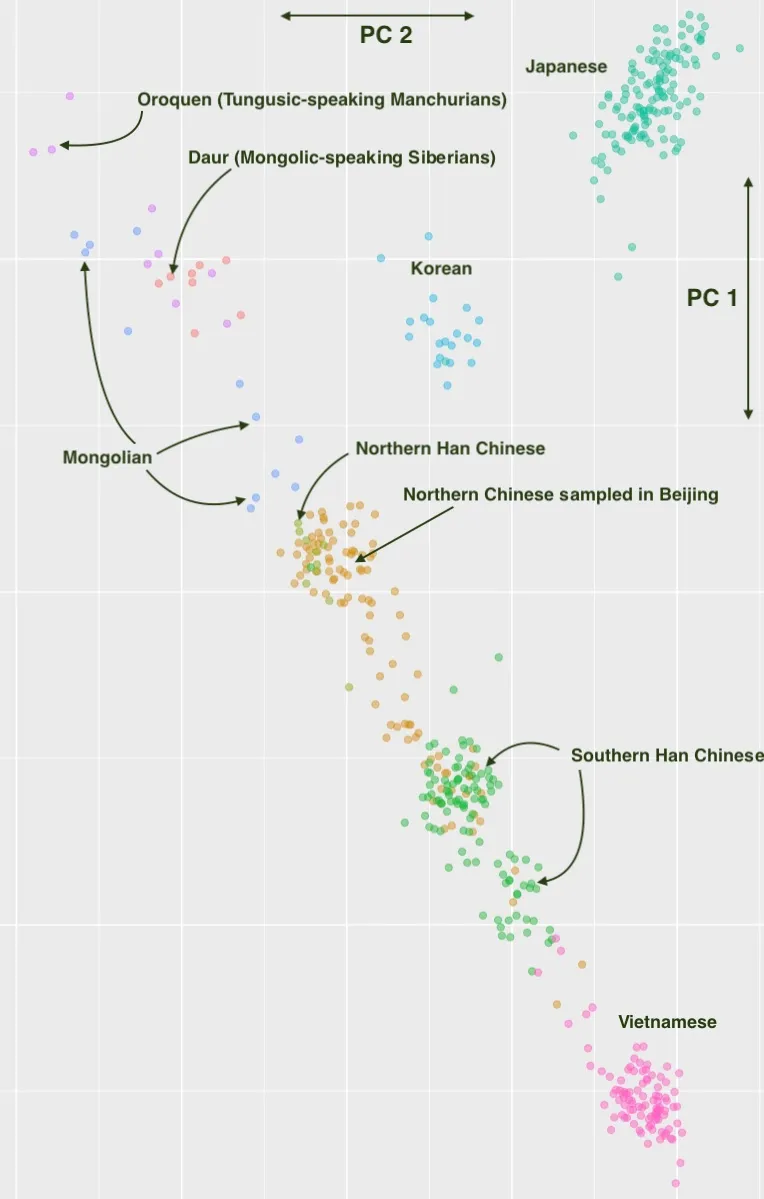

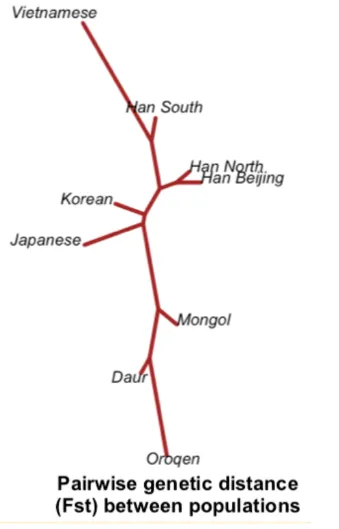

But before we further unpack the Korean genetic past, let’s look at how Koreans relate to their regional neighbors genetically today. To consider this question, I assembled a dataset composed of 20 Koreans (of South Korean heritage), 103 Han Chinese sampled in Beijing, 10 Han from northern China and 105 from southern China, as well as 132 Japanese and 9 Daur, 12 Mongols, 9 Oroqen and 99 Vietnamese. With 60,000 common markers on each typed individual, is more than enough data to run a principal component analysis (PCA) relating individuals to each other on a two-dimensional plot, and to generate a pairwise genetic distance between groups using the Fst statistic (represented by a neighbor-joining graph that visualizes the distances).

The first thing to observe about the PCA plot above is a cline running north to south in East Asian populations. The antipodes of the range are, at one end, the Daur and Oroqen, northern Manchurian and Siberian tribes respectively, and at the other, the Vietnamese, who reside in tropical Asia. The order of populations is geographically coherent: the Oroqen of Manchuria and the Daur of Siberia, Mongolians, northern Han Chinese, southern Han Chinese and the Vietnamese. But perpendicular to the primary north-south cline are the Koreans and Japanese. More precisely, Koreans are positioned between the Japanese and the non-Korean mainland populations, in particular, northern Han. Of course, this is also where they reside geographically: at the interstices of Manchuria, China and Japan.

The pairwise Fst, which summarizes genetic differences between two populations, recapitulates the pattern you see in the PCA. In the PCA, individuals mostly cluster neatly into distinct populations that correspond to the categories in the pairwise Fst. When the pairwise genetic distance is visualized on a neighbor-joining tree, the Vietnamese fall at one pole of the twig-like tree, with the Oroqen at the other. Japanese and Koreans are distinct, out on slightly longer stems branching off in quick succession, while Han populations show the expected variation between north and south (southern Han are closer to Vietnamese, northern Han to Koreans and Japanese).

The simplest demographic model which explains these genetic patterns involves serial migration and isolation by distance, dynamics which perhaps sound more complicated than they are. In essence, imagine an evolutionary phylogenetic tree and overlay it on a geographic map, adding arrows to the tips of the phylogeny, converting them into migratory vectors. Concretely, this means that when modern humans arrived ~45,000 years ago to East Asia in a single wave, some groups moved northward, enduring a population bottleneck and a subsequent split at each step. The demographic dispersion across a landscape with geographic barriers like rivers and mountains means genetic differences will accumulate between groups with shared ancestral origins. Accumulated genetic variation, represented in statistics like pairwise Fst, then is a natural outcome of human expansion and diversification that we can detect statistically, without any knowledge of precise historical details or specific events required.

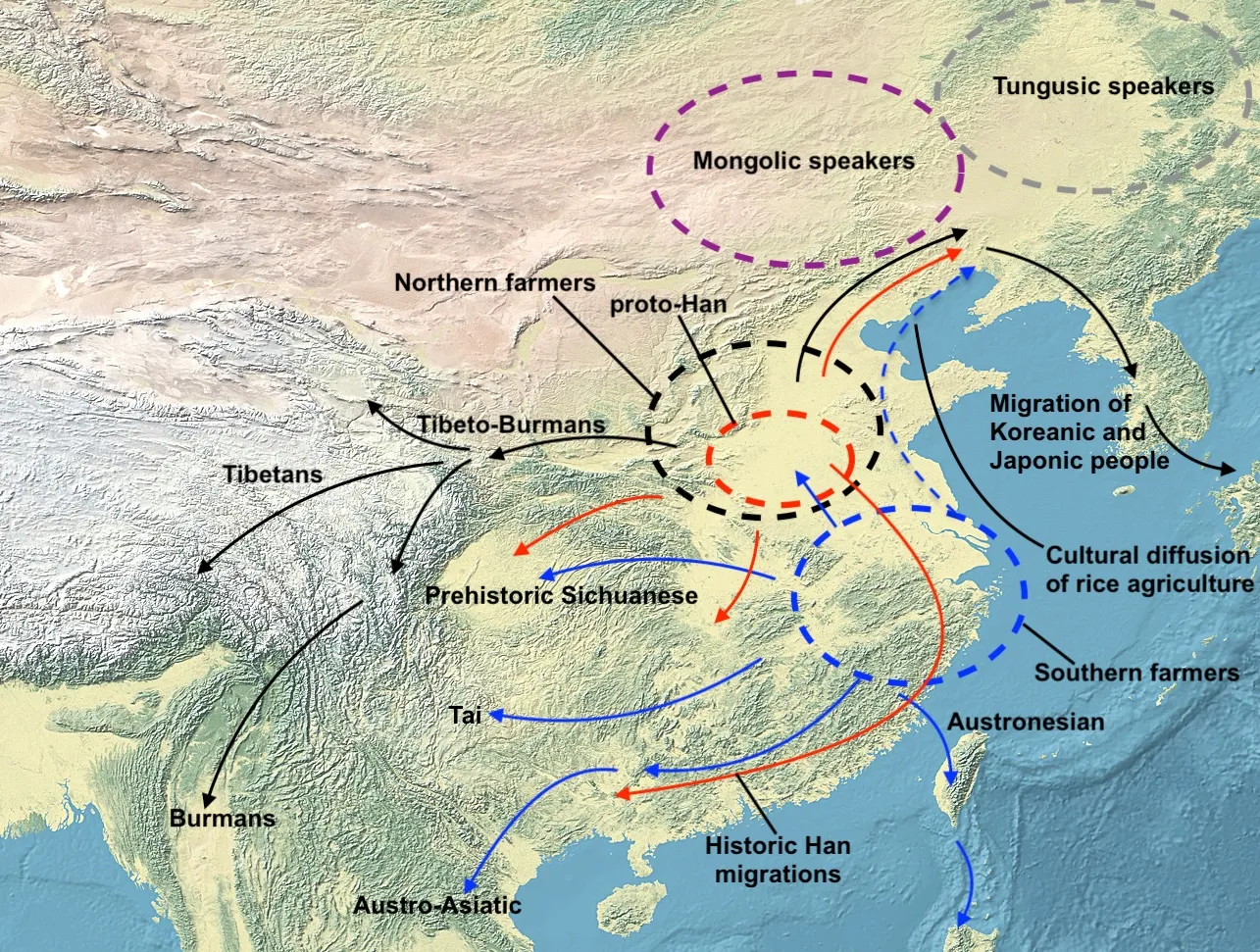

The problem is that though the model is elegant, we have enough data to know it’s not true. Biology isn’t physics, historical contingency matters, and populations don’t just migrate unidirectionally forever like lost moons hurtling out of the oort cloud, branching outward and never looking back; Neolithic-era humans brought rice farming to Southeast Asia, reversing the initial anatomically modern human north-to-south direction of migration from Southeast Asia to China (ancient DNA and archaeological evidence can even date the arrival of northern agriculturalists to modern Hanoi’s environs about 4,000 years ago). At some point, China’s Yellow river basin agriculturalists expanded back westward toward the Yellow Sea coast from which their ancestors had come. At the same time, these people were expanding in the other direction, pushing into the uplands of Tibet, transforming the genetics of a region previously occupied by foragers who had earlier percolated up from Southeast Asia. Finally, +Austronesians sailed out of Taiwan across Southeast Asia, and eventually across the Indian Ocean and back to Africa itself, leaving a permanent cultural and genetic legacy in ~Madagascar. The tips of the evolutionary tree don’t split indefinitely, repeatedly we see distant branches have been grafted back together in what were surely fraught reunions after long separation. The modern Han Chinese, who descend from the Erlitou culture of Henan that flourished 4,000 years ago, are one such fusion; scions of both northern foragers who ranged from the Yellow river plain in the west to the Liao river basin in the northeast, and southern hunter-gatherers who traversed the Yangzi basin and haunted southern China’s coastlands. The tree of humanity is really a gnarled bramble. Again and again, since we entered the age of massive genomic sample sets, we are reminded that a pinch of data is worth a pound of theory.

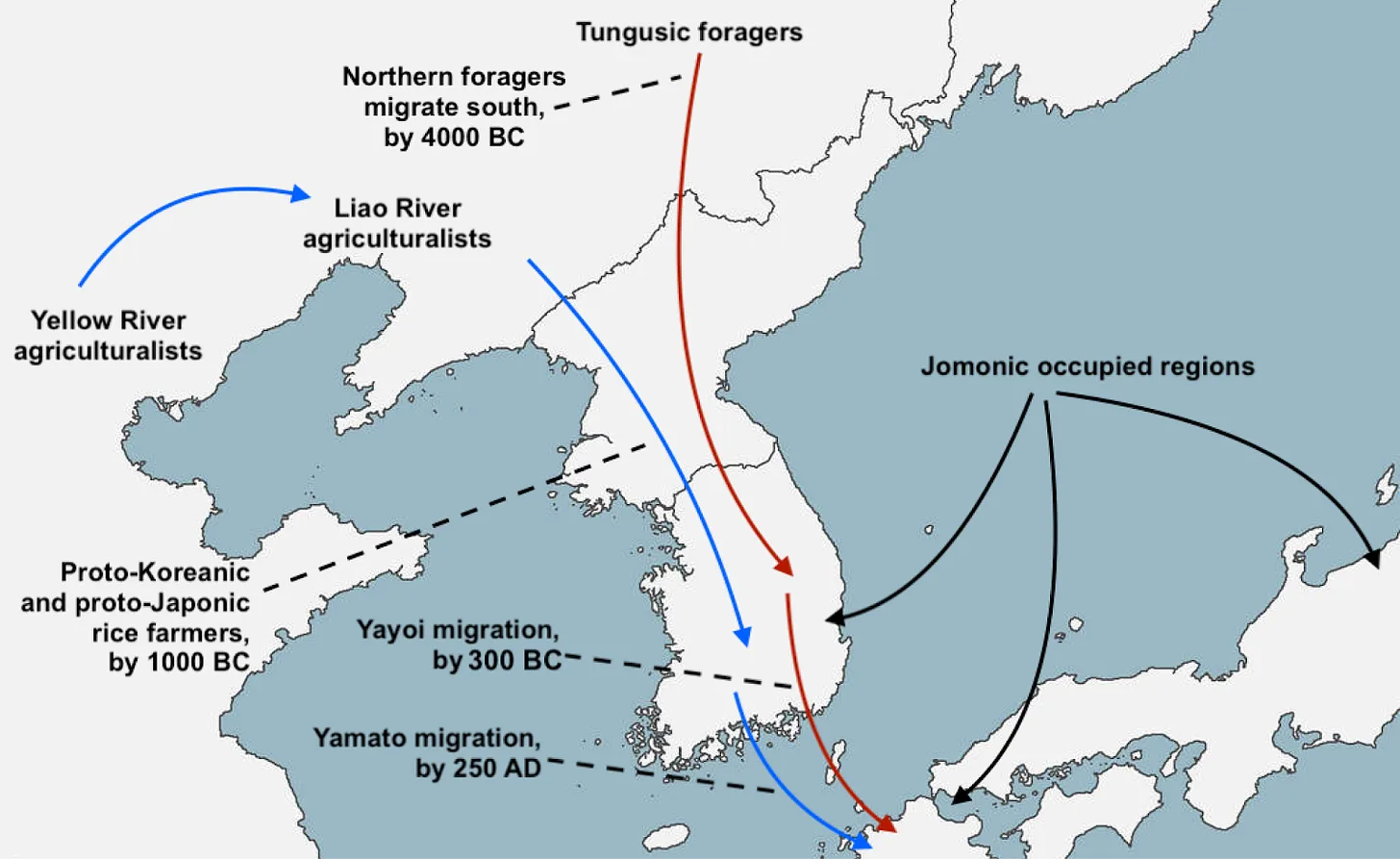

The Korean peninsula’s location puts it at the nexus of these various late Ice–Age populations coursing west to east and north to south. While the foragers of the Yellow river plain settled down to become farmers after the last Ice Age, to the north, in Manchuria’s forests and along its icy rivers, nomadic hunters continued to hone their skills, perfected under brutal conditions that had prevailed for 100,000 years. Further south, prehistoric foragers in the Korean peninsula developed a signature pottery style 10,000 years ago, very similar to that of contemporaneous Jomon-period artifacts in Japan. This affinity of style is almost certainly due to a shared origin among the broad network of Siberian people who had pushed eastward more than 20,000 years ago, before the peak of the last Ice Age. In Japan, these people became the ancestors of peoples known as the Ainu, but in Korea they disappeared early on in prehistory. Koreans notably were rice farmers by the time they enter the Chinese historical record 2,000 years ago, not Paleo-Siberian foragers. And rice agriculture has its origins far to the south, in the Yangzi river basin. Some historians and archaeologists have posited a seaborne migration out of the south seeding rice culture in both Korea and Japan. But the genetic and archaeological data refute this theory. Rather, a new form of pottery that spread across the peninsula around 1500 BC and arrived at the same time as rice farming derives from traditions in the Yellow and Liao river basins, pointing to an origin due west, not south.

In fact, modern Koreans descend preponderantly, as we will see, from millet farmers who adopted agriculture in the often cold and dry central Yellow river basin. Only later did they switch to rice cultivation, as they drifted eastward into the Liao river basin, before finally penetrating the peninsula’s northern reaches. Reflecting these peripatetic migrations, Korea’s earliest polities spanned the peninsula and southern Manchuria, with Koguryo’s western boundary being the Liao river itself. Given such vast territories it is no surprise that Koguryo integrated northern Manchurian tribes like Buyeo into both the ruling and ruled classes.

South of the north

Manchuria, named after the Tungusic-speaking people long resident in the region, is today divided between the Chinese provinces of Heilongjiang, Jilin, and Liaoning. Liaoning, furthest south and west, harbors the historically important Liao river basin, the gateway to the plains of northern China to the west and the Korean peninsula to the east. Before Koguryo’s 666 AD defeat by a Tang Chinese invasion and later Silla’s assimilation of the northern polity, its territories were imperial in their scope, spanning Jilin, Liaoning and northern Korea, with its capital in today's Pyongyang. Today the Yalu river famously marks the boundary between Korea and Manchuria (or alternatively, North Korea and China); it was here in 1950 that General Douglas MacArthur’s troops confronted the massed formations of the People’s Republic of China’s army, which swooped in on behalf of the Korean Communists when they were on the verge of defeat, having retreated to Korea’s northernmost fringe. For Koguryo though, the Yalu was not a barrier; it was the artery of a vibrant multiethnic state that extended deep into the heart of Manchuria.

The road to the ethnogenesis of modern Korea seems to have run through the north, from boreal forests on the banks of the Siberian Amur river, home to hunter-gatherers and tigers, to the fertile Liao River’s clement banks where farmers tended rice paddies. This seems to be hinted at in the PCA above, with Koreans “pointing” to the North Chinese on a transect from Japan. Today, Manchuria is mostly inhabited by Han Chinese, who became the region’s dominant ethnicity by the 19th century. But previously, under the ethnic Manchu Qing dynasty, the region was inhabited by numerous peoples, Chinese, Koreans, Tungusic tribes like the Manchus, and Mongolic peoples like the Khitai, ancestors of the modern-day Daur. Even today Manchuria’s relative pluralism, home to half a dozen Chinese national minorities as well as the Han, is a contrast to the peninsula to the south that has been linguistically homogeneous for nearly 1,000 years, with only two languages spoken in either of today’s Koreas. These are Korean and Jejum, the latter of which is spoken on the island of the same name to Korea’s south; curiously, these Koreanic languages are linguistic isolates, unrelated to any tongues outside their family, despite genetic and cultural connections to the north, west and east.

Korean and Jejum are neither part of the broader Sino-Tibetan language family, nor are they related to Japanese. Attempts have been made to fit them into the broader Altaic language family, which at its most capacious would include Turkic, Mongolic, Tungusic, Japonic and Koreanic. But this language family has little scholarly consensus in its favor as a genetic coherency. And language is of little help in answering the key ethnic question: do Koreans align with the northern Siberian-adjacent Tungusic and Mongolic peoples, or more with the southern populations of agriculturalists, of which the Han Chinese are the primary exemplar? Many Koreans believe in connections to other northern peoples due to legendary myths of descent from semi-historical peoples like the Yemaek tribe, whose territory included much of southern Manchuria, and who were integrated into trade and cultural networks of neighboring Tungusic and Mongolic tribes. Certainly Mongolians have strong views on their deep affinity to Koreans.[2] About a decade ago, when the Mongolian Nazi Party was perpetrating (see ) anti-Chinese violence, Han Chinese visitors to Ulan Bator made a point of identifying themselves as Korean, because Mongolians viewed Koreans, unlike the Han, as part of their broader ethnic family. In Korea’s national mythic history, put down in writing 700 years ago, their founder was Dangun, who descended from Heaven 4,333 years ago. Intriguingly, Dangun is a cognate of Tengri, the Turkic-Mongolian sky god worshiped by Genghis Khan.

As with many aspects of modern human population genetics, our newly granted powers to dig into prehistory are often the surest way to illuminate the present, and question the assumptions of the past. To test the prehistoric affinities of Northeast Asians, including Koreans, two 7,700 year-old samples from the Amur river valley in far northern Manchuria were sequenced in 2017, and compared to modern populations in the region. These two individuals exhibit a very northern East Asian genetic profile, and are part of the ancestral population that contributes most of the ancestry to the Tungusic people who reside in northern Manchuria to this day, highlighting genetic continuity in the region over the whole of the Holocene. But only a minority of the ancestry of modern Koreans derives from the populations resembling ancient or modern Tungusic people. The northern vector seems to be a secondary factor, despite long-term historical and cultural interactions. Though Koreans are not directly descended from Han Chinese (and indeed, do not even speak a Sino-Tibetan language), over 60% of their ancestry derives from the same pool of farmers who were expanding in all directions out of Bronze-Age northern China. The Han Chinese would prove the most demographically successful of these peoples, destined to expand outward and become the most numerous ethnicity in the world. But before the Han expansion 3,000 years ago, farming populations with a different cultural background seem to have raced ahead of them eastward, first colonizing the Liao river basin, there switching from millet to rice, before making the final push southward to Korea and later eastward to Japan.

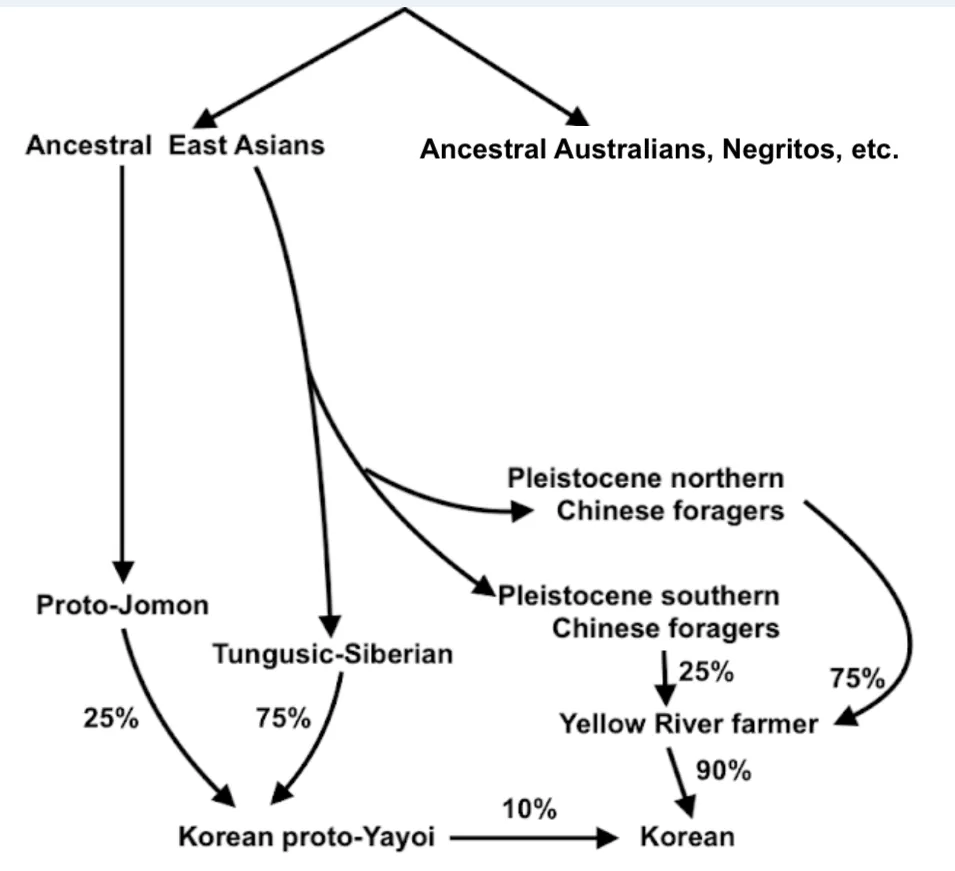

But these people did not expand into a vacuum; earlier groups occupied Korea and Japan. The PCA position of Japan in relation to Korea is only comprehensible when taking into account this fact: modern Japanese retain about 10% Jomon ancestry, the Ice-Age Paleo-Siberian population long indigenous to the islands (the common Japanese Y-chromosomal haplogroup, D is almost certainly Jomon). The foraging lifestyle of the Jomon was disrupted by rice-farming newcomers, called the Yayoi, 2,300 years ago. Archaeologists had long believed the Yayoi to be the ancestors of modern Japanese. But in a recent plot twist, paleogenetic analysis of Yayoi burials now shows they are not[3] ancestral to modern Japanese nor Koreans, but genetically closer to Manchuria’s Tunguisic and Mongolic speakers. Instead, it was in the first few centuries of the Common Era, less than 2,000 years ago, that we finally saw the arrival of a people genetically similar to modern Japanese (and thereby, Koreans).

This implies certain realities about Korean population history, even if the textual sources from the peninsula are patchy and confused during this period. First, by geographical necessity the Tungusic-Mongolic-related ancestors of the Yayoi must have arrived in western Japan 2,300 years ago via Korea. So even if modern Koreans do not resemble their northern Manchurian neighbors, some ancient Koreans must once have, perhaps explaining cultural memories of ancient connections. Second, another population genetically much closer to modern Koreans followed in the Yayoi’s wake, ultimately absorbing the earlier wave of migrants and the indigenous Jomon. Geography also dictates that it would have been via Korea that the earliest group, the hunter-gatherer Jomon, arrived in Japan out of Siberia. They had settled Japan at the latest by the Last Glacial Maximum 20,000 years ago, after which land bridges that made it possible to walk overland from southern Korea to Honshu disappeared under rising sea levels. These were the original foragers dominant in the peninsula at the beginning of the Holocene, before the arrival of rice farmers, whose cousins were also ascendent across the Korea Strait.

So perhaps it is useful to consider that, before the Japanese were Japanese, they were Korean. And because Japan is a product of Korea, to understand Japan is to better understand Korea. When Silla unified the Korean peninsula in the 7th century AD, it was still not entirely ethnically Korean. Evidence of Japonic people in that era in modern Korea is visible if we just look, which hints at intriguing ties of ancient peninsular peoples to their contemporaries in Yamato-era Japan.

The Lost Kingdom

At the dawn of its history, with the Yalu river far behind us, descending into the heart of what is now South Korea, the Korean peninsula’s ethnographic and geopolitical landscape would have felt startlingly unfamiliar. Instead of a united nation loosely ringed by larger neighbors, Korea was divided among itself. Silla’s expansion in the middle of the first millennium AD came at the expense of two other polities in southern Korea: Paekche and Kaya. Paekche was often in alliance with Yamato Japan, while Silla, positioned to its east, allied with Chinese powers further to the west, across the Yellow Sea. Eventually Pakeche’s geopolitical position became untenable, and it was conquered by Silla, notwithstanding Japanese intervention. The smallest of the southern polities, Kaya, meanwhile, was not a unitary state, but rather a confederacy of even smaller principalities. Though sources are thin, they suggest Kaya was inhabited by people who did not speak Koreanic languages and were culturally quite distinct from Silla, Paekche and the Korean ruling class of Koguryo. As late as 1000 AD, under the subsequent Koryo dynasty, observers reported linguistic diversity in the Korean peninsula’s southern reaches that by the Choson period had long since faded away.

That diversity is now reflected in genetics. A recent ancient DNA paper examined samples from eight individuals dating from the 4th through 5th centuries AD from Gimhae, a major city in Kaya prior to the Silla conquest. Two primary results stand out. First, all the individuals had detectable Jomon-like ancestry[4]. Six of them at levels comparable to modern Japanese. But two of them have Jomon-like ancestry levels as high as 35%, higher than any individuals found in East Asia today (with the possible exception of a few Ainu, the indigenous people of Japan’s Hokkaido)[5].

An earlier paper using a diverse array of genomes that included Neolithic and Bronze Age Koreans also found individuals with large amounts of Jomon-like and northern Asian Tungusic-like ancestry present in southern Korea before 2000 BC, prior to the arrival of rice farmers. In the later Bronze Age, these people were then replaced by the rice farmers migrating out of the Liao river basin. This last wave, the genetically dominant component in both modern Koreans and Japanese, brought both the Koreanic and Japonic language families to the peninsula more than 3,000 years ago. But both in Korea and Japan, earlier ethnolinguistic regimes persisted down to 600 AD, in the shape of the Kaya confederacy in Korea, and among the notoriously hirsute Emishi tribes of northern ~Honshu in Japan.

One perhaps less satisfying explanation for the genetically anomalous samples from Kaya is that they were just descendents of Japanese colonists; a reverse migration. But the genetic analysis that dates the admixture of various ancestral components in these ancient Koreans puts the amalgamation of Yellow river ancestry with Jomon-like heritage in their genomes at around 1500 BC, a millennium before the arrival of the first rice farmers to Japan. Far more likely is a scenario where the Korean peninsula underwent similar dynamics of admixture and replacement to Japan, but a millennium prior, and with every trace of it subsequently erased much more thoroughly in the historical record. First, the peninsula was dominated by Jomon-like peoples, and then Tungusic peoples, whose origins are further to the north, in Pleistocene Siberia and post-Ice Age Manchuria, respectively. These tribes were totally assimilated, both genetically and culturally, into the masses of western-origin rice farmers who were distantly related to the Han Chinese, the people who arrived with the full package of proto-Korean and proto-Japanese culture 3,500 years ago. Subtle variations distinguish the two narratives of the Koreans and the Japanese; the Japanese still differ from Koreans in that their northern Siberian affinities are stronger. The Yamato people’s ancestors migrating from Korea already carried Jomon-like and Tungusic-like ancestry before they assimilated the Tungusic-like Yayoi and Paleo-Siberian Jomon people of the islands, adding an extra dollop of admixture above and beyond what the Koreans had. Aside from the conquest of Kaya, we have little understanding of how Japonic people were assimilated by the early Koreans, but medieval Japanese battles with the barbarian Jomon-descended Emishi tribes in northern Honshu before 1000 AD underscore that conflict was likely part of the story.

in and out migrations of Korea

Korea before Koreans

The Silla conquest of the Korean peninsula in 668 AD was just the beginning of making Korea Korean. While later dynasties like the Choson emulated Chinese bureaucratic meritocracy, standardizing and homogenizing society consciously, the Silla were less self-aware. Despite strong Chinese influence in their culture, including the introduction of bureaucratic examinations, the Silla were still a highly lineage-focused semi-tribal society, more a collection of warlordships than a centralized top-down administrative state in the vein of Imperial China or later Choson Korea. Silla was proto-Korean in culture and ethnicity, but it was a much more open society than later Korea. The ruling family of Kaya, who were not ethnically proto-Korean, and had a cultural and genetic affinity to the Yamato people of Japan, seamlessly integrated into the ### A Northeast Asian map of Korean genealogy of class hierarchy that organized status and power in Silla. Silla mixed its blood and prestige with that of conquered Kaya, creating the basis of what became properly Korean as opposed to merely Koreanic-tribes and principalities.

Despite its relative cultural pluralism, one of Silla’s greatest achievements was to break the geopolitical ties between the people of the peninsula and the islands of Japan. The Battle of Hakusukinoe in 663 AD, when Paekje and Yamato Japan fought Silla and lost, was the last major Japanese engagement on the Korean peninsula before Hideoyoshi Toyotomi’s 1592 invasion. Before Hakusukinoe, the Yamato people seem to have been regularly involved in Korean wars, usually taking the side of Paekje and Kaya against Silla.

These issues are fraught because during Japanese colonialism such connections were opportunistically unearthed to justify Korea’s integration into the Japanese Empire. Here, the smallest linguistic choices are freighted with political significance. The Koreans refer to Hakusukinoe as Baekgang, and the Japanese call Kaya the state of Mimana. Japanese propagandists clearly overread and overemphasized the ties between southern Korea and ancient Japan, but the textual history, archaeology and basic geography reflect a reality of reciprocal connection and long-standing entanglement. Korea was long at the center of ethnic and geopolitical conflict in antiquity. As Japan became, Korea had been. Foragers genetically similar to the Ainu, the prehistoric Paleo-Siberians, called Jomon in Japan, inhabited both these nations at the beginning of the Holocene, 11,700 years ago. At some point before the arrival of rice agriculture 3,500 years ago, Tungusic foragers also began to migrate southward out of northern Manchuria, following the precedent of their distant Paleo-Siberian cousins. Some of these Tungusic people shifted to agriculture, likely a consequence of their interaction with the cultures of the Liao river basin west of northern Korea. But after 2000 BC, the Liao river basin, southern Manchuria and northern Korea were all demographically overwhelmed by rice farmers from the west, bringing with them linguistic and ethnic diversity that in their ancient homeland would be submerged by the rising tide of Han Chinese.

Genetically similar to each other, the Yellow river agriculturalists were nevertheless culturally divided. Out of this agricultural hearth arose the ancestors of the +Tibetans in the far west, Han Chinese at its heart, and the forebears of the Korean and Japanese-speaking people in the east. While Tibetan is related distantly to the Han Chinese language, the languages of the Koreans and Japanese are not, nor is either particularly related to the other. In addition to being polyglot from the beginning, ==the all[6] Yellow River agriculturalists were also very culturally adaptable; the central and western peoples remained wedded to millet, but later switching to wheat, while the tribes who moved eastward adopted rice agriculture, which was more productive in warmer, moister climes. ==

The demographic patterns inferred from genetics allow us to finally begin to establish a broader meta-narrative that encompasses northern Northeast Asia, with Korea in the center. The early history of Korea and Manchuria more than 2,000 years ago is known from the annals of the Chinese, which record Gojoseon and Jin in the north and south of the peninsula, along with other barbarians like the Xianbei, Wuhuan and the Buyeo and Yemaek. The ethnographic atlas is spotty and we are feeling our way through the retreating darkness, but the arrival of genetically Korean-like people to Japan in the first few centuries AD confirms the existence of a reservoir of Japonic-speakers in the southern Korean state of Jin. Centuries later, these Japonic Koreans evolved into the Kaya confederacy. Kaya’s fall to Silla ultimately spelled the cultural death knell of the Korea of many peoples. In its place arose an enduring Korea of Koreans.

Latin replaced all the other languages of the Italian peninsula upon Rome's rise, eventually spreading all across Western Europe. Similarly, 1,400 years ago the ancestor of today’s Korean swept away all other competitors, becoming the language of the people and state that would unify the peninsula. Whatever remnant Tungusic element existed in the northern polities of Korean states crushed between peninsular Korea and Manchuria, or the presumed Japonic component in Silla, these were eventually fully absorbed and assimilated. The underlying genetic variation remains, an indelible memory of past history, but a millennium of Confucian Korea, centralized, organized and systematized under elite mandarins has decisively smoothed away and overwritten that long ago complexity.

In a land that still awaits reunification 70 years after the end of the +Korean War, an exceptionally monolithic and enduring national identity meanwhile owes to homogenizing processes begun some 1,400 years ago with Silla’s decisive conquests of the peninsula.