Lost Green Saharans: ancient DNA unearths a new race from a verdant North African interlude | Razib Khan

These 7000-year-old humans are neither Eurasian nor sub-Saharan African

body

Guelta d'Archei: an oasis in Chad that is one of the last surviving remnants of the ancient Green Sahara ecosystem

Remember how simple our story used to be? Twenty-five years ago, our line was that the fateful lineage leading to us, the anatomically modern populations who dominate the planet today, began with a big bang about 200,000 years ago. A single massive wave like a demographic tsunami rushing concentrically outward swept away all competing branches of humanity, snuffing out their separate flames, mercilessly pruning so many disparate branches from the vast and ancient tree that stretched back over a million years to the roots of our hominin lineage. Today, a generation on, by the light of incessant bombshells of insight from computationally powered modern genomics and the laboratory wizardry of paleogenomics, our simple story is long gone; and every few years seem to produce yet another verified side plot or narrative twist to complicate the story of us. Our terse Hemingway novella insists on becoming a sprawling 19th-century Russian epic, its confoundingly complex plotlines interweaving across continents and epochs.

Perhaps we shouldn’t be surprised. With the relatively small data sets of the late 20th century, it stood to reason that our best models would be simple, too. When raw material is sharply constrained, the edifices produced tend towards minimalism. Today, with the whole genomes of thousands of ancient humans, including from three major lineages, Neanderthals, Denisovans and the African populations that led to all of us, we are no longer constrained by a lack of relevant data. A vast theoretical cathedral is now being erected, no rude preliminary sketch, but a detailed demographic simulacrum of what once was, the dream of eventually working out every detail and nuance more fathomable by the day.

Much of the story to come in the next few decades of human population genetics will unfold in sub-Saharan Africa, as our tools and methods rise to the challenge of illuminating our deeper origins. But though Africa south of the Sahara is the site of most of our species’ evolutionary history, today we’re adjusting to a revelation not out of the cradle of humanity, but from the sands of the continent’s largely barren northern third.

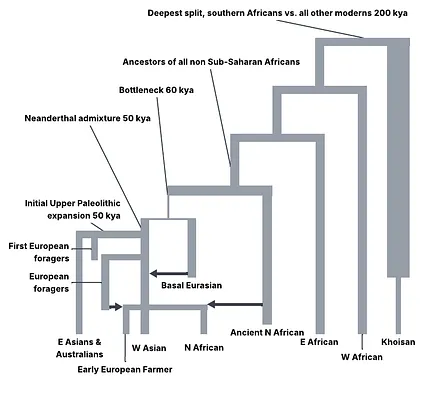

In 2000, the plot was dead simple. A small group of expansionist East African modern humans left the ancestral continent 50,000 years ago, and exterminated all of our cousins, from the Neanderthals in Europe to assorted other hominin populations (these latter at the time unnamed) in East Asia. By 2010, it became clear that the extermination had not been complete; non-Africans carried Neanderthal heritage from an admixture event early in the out-of-Africa migration timeline, likely in West Asia. More surprisingly, we also harbored Desinovan ancestry, traces of an eastern human species that was discovered solely by genomics. And the surprises kept coming. In 2014, geneticists scanning patterns of relatedness across ancient and modern humans realized there had been a branch of non-Africans who never mixed with Neanderthals, and whose heritage many West Asian populations carry. This heritage was also brought to Europe and South Asia during the agricultural revolution’s demographic expansions starting 10,000 years ago. We termed this population “Basal Eurasians,” for their early split from other non-Africans, over 50,000 years ago.

But, like all other non-Africans, Basal Eurasian genes attest that that group too is a product of the “great bottleneck,” a period of thousands of years when the ancestral breeding population of all humans except sub-Saharan Africans collapsed to the scale of just some 1,000 individuals, give or take. It seems likely that Basal Eurasians 50,000 years ago occupied territory in West Asia or Northeast Africa, so they never had a brush with Neanderthals, like their non-Basal cousins, who pushed north and east into the highlands of Iran and the Caucasus. There, our ancestors absorbed a large population of Neanderthals before sweeping outward to the north, northwest and east, taking their Initial Upper Paleolithic (IUP) toolkit all across Eurasia and onward to Australia. The story then, until 2025 ran that the “out of Africa” humans had developed in isolation, and a branch had eventually gone on to conquer the world. This small out-of-Africa population was one of multiple human groups who branched off from Africans south of the Sahara, specifically from East Africans.

Recently, that story has received a significant plot twist. Early modern humanity was a bigger family than we thought. Over 50,000 years ago, the ancestors of today’s humans were divided not just between sub-Saharan Africans and proto-Eurasians, but into at least three broad categories, because now paleogeneticists have uncovered a lost branch of humanity that long occupied northern Africa, separate and distinct from the sub-Saharan populations to their south, and the Eurasians to their east. These were the Ancient North Africans (ANA), and we now have three genomes where this exotic heritage predominates, their 2025 publication opening a new chapter in the quest to retrace the human journey at a level of granularity unimaginable in 2003 when the site was first excavated.

The other Africans

The unwieldy term sub-Saharan African encompasses all the variegated peoples south of the Sahara desert. A simpler label might be black Africans, but populations like the San foragers and Nama pastoralists of southwest Africa have lighter skin than many tropical Asian peoples. An essential aspect that has set sub-Saharan African population structure apart since the emergence of molecular evolution in the 1980’s is that it remains the most genetically diverse on the planet because its peoples alone were spared the great bottleneck that all other known humans endured (or so we thought). This has preserved such wealths of genetic diversity that we find the Khoisan of the far south are genetically more distinct from West Africans than West Africans are from Eurasians (who are, of course, ultimately descendants of East Africans). The cleavages within Africa are deepest and most ancient in the south, but now new light has been shed on the oft neglected north, which in our day is mostly uninhabitable desert.

An April 2nd, 2025 paper in Nature introduces us to an additional population that also skipped the great bottleneck, and also were not sub-Saharan Africans. The paper is Ancient DNA from the Green Sahara reveals ancestral North African lineage. This finding is not a total shock, a 2018 paper reporting seven 15,000-year-old samples from what is today Morocco found only an imperfect fit between them and contemporary populations in the region. Located in Taforalt cave, these individuals’ genomes bore affinities to Near Eastern populations, but gave perplexing signs of genetic variation that didn’t really fit any of our existing models of human evolution or the representative list of populations then in our datasets. The challenge with the Taforalt samples is that it’s hard to understand admixed populations without a good grasp on the putative source populations in the first place. Imagine trying to solve for x in the equation 2 + x = 6 if you know no numbers beyond 2. It just doesn’t compute.

Takarkori rock shelter

The Nature paper genotypes three individuals from 7,000 years ago in the deep Sahara, in southwest Libya. These new probands were much more geographically and genetically isolated than Taforalt’s Pleistocene Moroccans, and the Libyan genomes offer much more unambiguous evidence of a previously unknown and distinct ancestral population that must have flourished across North Africa for tens of thousands of years prior. The Taforalt individuals were the first clue that our existing understanding of African population history had serious gaps; prehistory north of the Sahara was more complicated than we had thought. Of the three individuals found in the Takarkori rock shelter in the Green Sahara paper, one furnished truly high-quality DNA yielding over 800,000 markers, and reflects 90% descent from a distinct North African ghost lineage that was neither Eurasian nor sub-Saharan African. Named TKK, this individual’s results make clear and indisputable that a lost race of our species once called the Sahara home.

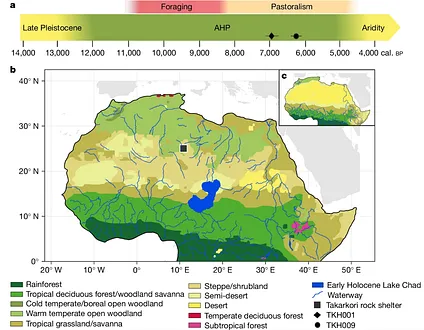

TKK and her lineage flourishing some 7,000 years ago in what is today deep in the heart of the world’s largest desert, are only comprehensible given the Sahara’s climatic fluctuations over the last few hundred thousand years. When TKK lived, the Sahara was not a desert across most of its range. The huge stretch of territory in Africa’s northern third from the Atlantic to the Red Sea was undergoing what is labeled in the paper the “African Humid Period” (AHP), another term for the more colloquial Green Sahara. As is clear in the map above, where inset panel C depicts the arid present and panel B represents the biomes of the wet period, between the end of the Ice Age 11,500 years ago, and 3000 BC, for these crucial millennia, most of the Sahara was not desert. It was instead a mix of woodlands, savanna and scrubland, with only a modest precursor of today’s vast desert along its eastern edge. Humid periods have punctuated the Sahara’s history since it emerged as a climatic and geological entity nearly 10 million years ago. The Eemian interglacial, dating to 110,000 years ago, may have been even more humid than the latest Green Sahara, thereby propelling human populations from the African core northward toward the Mediterranean.

But on a shorter time scale, before the reemergence of wetter conditions in the Sahara, beginning 14,500 years ago, the desert was actually larger and drier than it is today. Its arid edge extended 500 miles further south. The savannas encircled the few fragments of Congo rainforests, which offered ecological refugia for moisture-loving species. In the north, humans only seem to have inhabited the coastal regions of northern Morocco, Algeria and Tunisia. The highlands in the interior of the Sahara that even today are cooler and more humid lose signs of human occupation after 60,000 years ago, indicating that for tens of thousands of years, the desert posed an insurmountable barrier to humans, with the possible exception of the Nile river valley in the east.

One of the sets of remains from Takarkori rock shelter

The Sahara’s aridification seems to roughly correlate with the bottleneck that Eurasian populations endured 60,000 years ago. We have neither the ancient DNA nor archaeological evidence to pinpoint the locale where our ancestors were when they endured this extended bottleneck, but its length and the population crash’s magnitude indicate that the proto-Eurasians then occupied a very constrained area. Likely some sort of extreme climatic shock persisted for millennia to keep their numbers in check, and isolated from other humans. Ironically, the clue of the Sahara’s aridity, beginning 60-70,000 years ago, is a clear candidate for the unforgiving worldwide climatic regime whose regional extremes could have driven our proto-Eurasian ancestors to the brink of extinction.

But the ANA’s own existence sketches a more nuanced and complex picture; both the great aridification and humanity’s fragmentation in North Africa and West Asia were processes that may have resulted in multiple related populations distinct from those of sub-Saharan Africa. Though the ANA derived from the same ancestral population of East Africans that begat Eurasians, their higher level of genetic diversity indicates TKK’s ancestors evaded the sharp population reduction and restriction that marks proto-Eurasian genetics. One hypothesis runs that proto-Eurasians were restricted to a much smaller area in the eastern Sahara or Arabia, while the proto-ANA occupied all of northwest Africa, the modern Maghreb, a biogeographic extension of southern Europe, which boasted extensive territories suitable for human occupation (and in keeping with their more westerly position, pure ANA had almost no Neanderthal ancestry). These questions will only be settled by discovery of more genomes, or an ANA whole genome sequence that would enable more detailed population-history reconstructions.

TKK, a nearly pure ANA, plays the same role in plugging gaps in our understanding of population history that the Mal’ta boy in Siberia did. Mal’ta was the first set of “Ancient North Eurasian” (ANE) remains we found. He died more than 20,000 years ago, but when his genome was sequenced in 2013, paleogeneticists immediately recognized that his population was a missing puzzle piece to our understanding of the full tableau of western Eurasian and New World history. About 15% of Europeans’ heritage is ANE, as is 35% of Amerindians’. These connections were long suspected, but Mal’ta’s genome made them plain as day.

Wodaabe tribe of Fulani

The ANA genome is already shedding new light on earlier findings. A recent paper on the pastoralist Fulani of the western Sahel hinted at an untraceable component in their ancestry, probably from the Green Sahara. It was always clear that the Fulani had some non-sub-Saharan ancestry, but attempting to model this element as purely Eurasian always failed. Now we know why; a substantial proportion of their heritage is ANA, meaning that these pastoralists have roots going back to the Green Sahara. Unsurprisingly, the ANA also contributes up to 20% of the ancestry to peoples of the Maghreb: Morocco, Algeria and Tunisia.

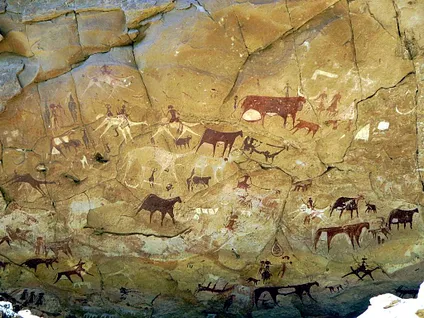

It is likely that the Green Sahara period was an ANA golden age. One of the questions this paper addresses is whether pastoralism spread in the Sahara via cultural diffusion or human migration. In the Sahara, before 5000 BC, we can now say it was clearly through culture. Only 10% of TKK’s ancestry is traceable to the Levant. The pastoralists whose petroglyphs bear testimony to a wetter, more bountiful Sahara were natives of the continent, not West Asian transplants. Likely though, their ancestors had drifted southward during the late Pleistocene from the continent’s northern fringe, where they had spent millennia isolated from both sub-Saharan populations, and their Eurasian cousins to the east.

Manda Guéli Cave in the Ennedi Mountains, northeastern Chad, 100 BC

Today the deep Sahara still carries the ANA’s legacy via the Tuareg nomads’ wanderings. But most of contemporary ancestry bears the heritage of later arrivals, who swarmed over the region after the end of the Ice Age. Most of the heritage north of the Sahara, along the Mediterranean’s southern shores, now traces back to the Levant, while sub-Saharan populations dominate many of the deep desert’s oases. Islam’s rise 1,500 years ago opened a new era in trans-Saharan gene flow, as black slaves arrived in great numbers on Mediterranean shores. Today people across the Sahara, including in the Maghreb, carry substantial sub-Saharan ancestry, but TKK and her kindred appear to predate contact with peoples to the south. Perhaps this reflected ecological separation and low population density; no matter the reason, the reunion of humanity’s branches across the barrier of the Sahara seems a feature of the last few thousand years alone, not of the Green Sahara epoch, which ran from about 3000- 14,000 years ago.

A tree with many branches

Until TKK was genotyped, the ANA were what paleogeneticist David Reich calls a “ghost population.” Like Planet X whose existence we intuit through its gravitational pull on other observable bodies, an ANA imprint was hinted at in Taforalt and many modern Saharan and Mediterranean genomes. But subtle hints take you only so far; the foundations of human evolutionary history require concrete genomes extracted from the remains of those who died millennia ago, those lucky random genetic snapshots from bygone ages. Only when we have an individual human’s genome extracted from ancient DNA does the history of a lost population become so visible to us, its light illuminating ages of prehistory that had been wholly hidden. The passage of time will likely deliver more genomes to flesh out the history of the ANA people. Was TKK part of a relict population unique for its high fraction of ANA, or actually typical of a broader set of peoples across the Sahara who for tens of millennia remained relatively untouched by both Eurasian and sub-Saharan heritage? We don’t know, but someday we will.

More generally, ANA reminds us how much we have yet to learn about the emergence of humans in the recent past. A well distributed sampling of ancient DNA now blankets Eurasia, informatively reaching deep into our past, but the subtropical and tropical zones have only ever been extremely lightly explored. Perhaps a day will come when we run out of genomes, but in the world’s torrid zones, today that is unimaginable: we’ve barely begun to look. Every new discovery brings the possibility that untold ghost populations, physically extinct, but with echoes possibly even discernible in our DNA, will join the human menagerie. Not long ago, we thought we had nailed down the full plotline of humanity’s emergence in Africa 200,000 years ago. But now we behold lost chapters buried deep in the Libyan desert, a genetic trove of unfathomed North African tribes neither black nor Eurasian, but humans on an entirely distinct journey altogether.